About EuroMCM

Classical inquiries into the knowledge of nature are often framed around three fundamental questions: what, how, and why. Each addresses a distinct yet interrelated domain of understanding. The question of what concerns the realm of technique and practical manipulation, while how belongs to the domain of technology, explaining the processes by which things operate. The question of why reaches into natural philosophy and theology, seeking the underlying reasons and meanings behind phenomena. Historically, these questions have been approached in sequence: first what, then how, and finally why.

Mathematical modelling occupies a critical position between how and why. It goes beyond empirical observation by translating observed mechanisms into formal mathematical structures that capture causal relationships with precision. In doing so, modelling transforms descriptive knowledge into explanatory and predictive understanding, uncovering the principles that govern system behaviour and enabling reliable forecasts grounded in theory rather than observation alone.

Early Foundations

Long before modelling became a formal discipline, European engineers used mathematics to address public works and scientific problems. In 19th-century France, the Corps des Ponts et Chaussées applied quantitative reasoning to infrastructure planning, while Jules Dupuit introduced early economic analysis of public projects, relying on institutional trust rather than formal optimisation.

20th Century Developments

In the early 20th century, biological modelling emerged as a new scientific approach. Building on earlier work by Alfred J. Lotka, Vito Volterra independently formulated the predator–prey equations in 1926, showing how interacting biological populations could be explained by nonlinear differential equations inspired by empirical observations of fish populations during World War I, while Nicolas Rashevsky extended mathematical modelling to cell division and neural networks, helping establish biology as a quantitative, model-driven science.

World War II marked a decisive turning point. The rise of Nazism forced many European mathematicians to emigrate to the United States, transferring applied mathematical expertise across the Atlantic. This group included John von Neumann, Jerzy Neyman, Abraham Wald, Richard Courant, Theodor von Kármán, Mark Kac, and William Feller. Their work consolidated applied mathematics, statistics, optimisation, and computing in the United States, reshaping global modelling practice. In economics, Gérard Debreu, trained in Paris, later introduced a rigorous axiomatic approach that transformed mathematical economics.

Modern Operations Research (OR) originated in Britain in the late 1930s, driven by the need to model radar systems, logistics, and resource allocation before and during World War II. Interdisciplinary teams such as Blackett's Circus combined physicists, mathematicians, engineers, and other specialists to analyse complex operational systems. These methods were transferred to the United States before Pearl Harbor and expanded rapidly in military, industrial, and governmental contexts.

After the war, modelling diverged according to political systems. In Britain, OR became closely linked to socialist planning and efforts to redesign government administration, though these ambitions declined during the Cold War as central planning became politically contentious. In the 1970s, modelling re-emerged at a global scale through the systems approach, notably in Jay Forrester's system dynamics and the Limits to Growth report for the Club of Rome, which applied mathematical models to long-term environmental and societal challenges.

From Industrial Mathematics to EuroMCM

By the end of the 20th century, mathematical modelling had become an interdisciplinary language for understanding and shaping complex systems in science, industry, and society, forming the intellectual basis for contemporary European modelling initiatives such as EuroMCM. From the 1970s onward, Europe's "mathematics for industry" movement developed from initiatives such as the Oxford Study Groups with Industry (1968) and culminated in the founding of the European Consortium for Mathematics in Industry (ECMI) following a landmark symposium in Amsterdam in 1985, aimed at bridging academic mathematics and industrial practice. A first-hand account of this development is provided in the talk by Professor Vincenzo Capasso at the ECMI 2012 Conference.

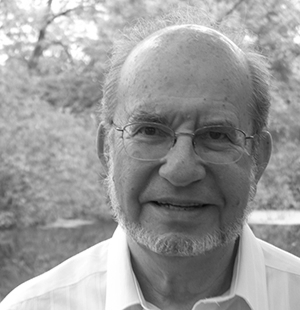

The European Mathematical Modelling Competition (EuroMCM) was founded to advance applied mathematics in the 21st century by uniting theoretical insight with computational practice. Initiated by researchers from leading European institutions, its preparation began in 2025 in dedication to the memory of Professor Haïm Brezis (1944–2024). EuroMCM carries forward his legacy by inspiring students to engage complex problems with rigour, clarity, and intellectual integrity. The community is invited to honour his enduring impact through our official tribute.

In Memoriam: Haïm Brezis (1944–2024)

EuroMCM draws inspiration from the tradition of open-ended mathematical modelling competitions, including the MCM/ICM organised by COMAP, while developing its own European academic identity. EuroMCM introduced a flexible team structure that permits cross-institute formation. This approach is designed to foster academic exchange and collaboration beyond institutional boundaries, aiming to strengthen connections within the mathematical community. Furthermore, in response to the evolving landscape of computational science, the contest incorporates modern AI problems. Participants are encouraged to utilise contemporary artificial intelligence methodologies developed in recent years to address complex, real-world challenges.

Competition Governance

The competition is governed by a three-part committee architecture designed to ensure operational effectiveness, academic integrity, and technical reliability. The Organizing Committee is responsible for logistical support, platform operations, and the global promotion of the competition. Academic oversight is provided by the Academic Jury Panel, composed of scholars with diverse academic backgrounds, which includes experience at institutions such as ETH Zurich, Imperial College London, Sorbonne University, Technical University of Munich, the Max Planck Society, and other leading European research centres, supporting rigorous academic standards for the competition. The Academic Jury Panel conducts independent evaluations under a double-blind review process; to preserve impartiality, jury members remain anonymous throughout the competition. In parallel, the Technical Review Committee is dedicated to enforcing strict academic integrity protocols through automated plagiarism detection and verifying the computational validity of top-tier solutions, ensuring that accepted submissions meet required standards of originality, correctness, reproducibility, and methodological soundness.

Prizes/Certificates

After the contest results are announced, all participants, including advisors and students, will receive a Certificate of Participation. Advisors can log in to the contest website via the Advisor Login link to view and print certificates for their teams. While the competition challenges are benchmarked at the undergraduate level, participation is open to students from secondary school through postgraduate stages. The results for the Undergraduate, Postgraduate, and Secondary School categories will be judged separately, with certificates of different result levels awarded accordingly. Certificates can be downloaded directly from the EuroMCM website. Each Special Award is granted to only one team within the Grand Prize level across all categories each year. The Special Awards include two General Problem Awards and seven Specialised Problem Awards. Additionally, the top three teams will each be granted a Haïm Brezis Scholarship, with the distribution between students and advisors following a 9:1 ratio. See Awards and Designations for details.